The recent gales have stirred angler’s interest as well as the seabed, with the cod hunters in particular desperate to get out and about on the beaches pulverized by the storm. However, in the wake of the big waves it is worth looking at the venue at low tide to see what effect the breakers have had on the underwater features and contours.

The power of the sea may not be able to move mountains but it can certainly shift the position of sandbanks, gulleys, rocks and in extreme cases large boulders. The constant thorough beating of the waves on a shoreline can substantially change not just the clean sandy areas but can bring down cliffs and shift kelp beds. Previously productive, fish holding areas may have been shifted or eliminated entirely and the angler who does not reconnoitre their chosen fishing mark may be casting their lures or baits over a barren area. The seas may also have brought new snags inshore or have strewn kelp and other tackle hungry weed over the seabed.

Thanks to Christian Bulch for the photograph

A visit to a beach after a big blow can produce a decent supply of bait as shellfish, razorfish in particular, are often dislodged from their previously safe havens in the sand as the wave action churns up the seabed. This supply of bait for the angler has the added bonus of being free feed for the fish and they will regularly move into an area to mop up after the winds have dropped.

What Are Waves?

Waves at sea are disturbances that cause energy to be transported through the water with little or no transportation of the water itself. In other words, although a wave can appear as a moving “wall” of water, the water molecules themselves are not being transported just their energy. Everyone will have seen the seagull sitting on the surface of the water bobbing about on the waves. The bird moves up and down as the waves pass beneath it but stays more or less in the same position.

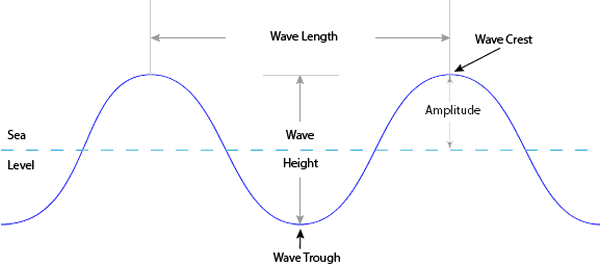

All waves have the same basic characteristics, the highest part of a wave is the crest; the lowest part is called the trough. The vertical distance between the wave crest and trough is the wave height and the amplitude, the maximum disturbance, is half this distance. The distance from a certain point on one crest or trough to the same point on the next crest or trough is the wavelength. The period is the amount of time it takes for succeeding crests to pass a specified point.

Wave Terminology

Most waves are formed by the wind when downdrafts depress the surface of the sea momentarily. A ridge and depression are formed and, like the ripples in a pond when a stone is dropped, the wave travels away from its origin. Smaller waves can catch up with each other and combine to grow larger.

Three factors control the size of waves:

- the strength of the wind;

- the duration of the wind;

- the distance of open water the wave travels, known as the fetch.

Generally, the coastlines facing the open Atlantic will experience bigger waves then those on the North Sea coasts due to the distance of open water out to the west of Europe. Due to its accompanying high wind strengths, a low-pressure system will generally produce larger waves than a high-pressure system.

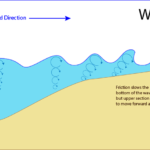

Why Do Waves Break?

Waves in deep water have a symmetrical “sine-wave” shape, where the crest and trough are smooth curves of equal size and shape. As a wave approaches the shore, the sea bottom depresses the trough, and the wave grows taller. At the same time, friction with the bottom causes the lower part of the wave to slow down while the top continues to move at the same speed. Eventually, the wave topples over or “breaks.”

The shape of the shoreline determines how a wave breaks. Shallow, sloping beaches cause waves to “spill” or gently break down the face. Slightly steeper beaches cause “plunging” breakers with a curling break or tunnel; these are the classic surfing waves. Beaches that are steeper still can create “collapsing” waves that break by falling all at once along the crest. “Surges” are very powerful waves that form on steep beaches during storms. They do not actually break; rather they heave or roll up the beach with tremendous force that can cause damage to property and shorelines.

A wave will generally break when the height of the wave is around 75 to 80% of the depth of the water, hence a one metre high wave will break when it arrives over a depth around 1.25 metres and a two metre wave when the depth shallows to 2.5 metres. As they break, the waves lose their energy that is lost as turbulence resulting in the stirring up of the sediments.

Shoreline Effects

In calm conditions, waves will deposit sediment on sand or gravel beaches as it falls out of suspension as the gentle flow of the wave, or swash to give it its technical name, moves up the beach. During high winds and storms, the breakers produce strong currents below the waves, the backwash, which draws the water, sand, pebbles and rocks back from the shore and causing erosion. The waves can substantially change the shape of a beach particularly during the winter months when winds are generally higher. A beach will normally be steeper shelving in winter than in summer.

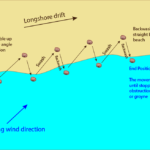

If the waves hit the beach at an angle a movement is set up which is known as a longshore current or drift. This drift causes a movement of sand and pebbles along the beach in the same direction as the wind and waves. This movement will only stop when it meets an obstruction such as a headland, breakwater or the groynes that are common on east coast beaches in the UK.

Extreme storms can completely destroy sandbanks situated at extreme casting range. On a longer time scale, waves also erode bedrock and sandstone cliffs, and create forms such as sea caves and sea stacks such as the Old Man of Hoy.

When wave approach a headland or approaches the shore at an angle the waves are bent or refracted towards the headland as the part of the wave striking the land slows rapidly, while the rest of the wave continues at its original speed. The converging waves on either side of the headland cause increased erosion which can form sea caves or arches. Conversely, the shallow areas between the headlands that form coves often result in small hidden beaches.

The Effect on Marine Life

Waves, combined with tides and currents, help supply nutrients to marine plants and animals that live along the shorelines. Waves push water up the shore and when the waves are higher than normal, they extend the intertidal zone farther up the shore.

As they carry sediment with them, waves affect the type of habitat that develops along a particular shoreline. For example, sand and gravel shorelines occur because waves and currents have eroded sediment from one source and deposited it another.

If a storm changes the characteristics of a beach from a gentle rise to a steep slope the intertidal habitat will be altered this may not only affect the fish habitats but also the availability of bait for the collectors. Weed dislodged by a storm and thrown up the beach will provide nourishment for shoreline plants and animals even if it is a pain when retrieving tackle.

Check The Effects

So before rushing out the door immediately after a big blow, take a bit of time and consider how the power of the waves may have affected your favourite venue. A quick survey at low water may save you fishing an unproductive mark or losing gear on snags which nature has plonked down right where you want your baits to be fishing.