Targeting and catching pollack with float tackle from a boat is a sure-fire way of maximizing sport and minimizing losses synonymous with other methods. Here Ian Lindsay explains the simplicity of this exhilarating tactic.

For years I wondered how I could be regularly mashed year in, year out by what I’d call big – say around 10lb – inshore reef pollack, yet I could look in an angling magazine and see some nine-year-old kid on his first boat trip with a wreck-caught 16-pounder. Then I spoke to Ian Burrett, undoubtedly the UK’s No. 1 small-boat charter skipper and a real specialist in pollack and tope. “You have to be a really good angler to catch a double-figure reef pollack,” said the wise Mr B, who like me is pursuing his pollack over hard, kelp-covered rock, and he’s right – inshore you will usually be fishing in shallow water, with a short line out and correspondingly less shock absorption; the fish will not be far from some rocky lair or other; they will not suffer from decompression and give up after one dive; and of course for optimum sport, you will almost always be fishing with light line and similarly light gear.

In other words, a reef pollack of even 8lb is an altogether different proposition to a bigger wreck fish taking heavier gear higher in the water, and I have enough sob-story notches carved into my rod butt to tell you that big inshore fish are wily characters who will find any flaw in light gear.

You see, the Catch-22 conundrum is this: give a wily old 10-pounder who’s lived over the same bit of rock for years his head, and he knows just where to dive for shelter. But do the opposite and try to hold him hard, and his first power dive carries enough clout to snap 20lb line, sometimes 30lb if it’s suffered a little abuse.

Float fishing is one way to increase your chances of landing such fish. Though less than foolproof, the method that works for me and the odds on landing an out-of-the-ordinary reef fish are definitely improved – and let’s face it, we need all the help we can get against such dirty fighters.

Depth-charged

For float fishing, start by setting the bait as high in the water as you think the pollack will be prepared to come. In my neck of the woods, eastern Scotland, I find that about two-thirds depth is the magic figure. Naturally, you can fish deeper or shallower, but deeper means the fish hasn’t come far from cover to take your bait, while shallower means it may well not bother. That said, pollack rise in the water table near dusk, and you should use that to your advantage by setting your bait to fish up a bit at that time, maybe as shallow as three feet sub-surface. Fishing deeper than two-thirds depth also leads to continual snagging – just because your sounder says 40 feet doesn’t mean there’s that much water where the float is fishing some way from the boat.

What you need to do is find yourself a really stupidly big float – not quite shark-size, but maybe a slightly OTT pike number. If you’ve seen the movie Jaws, you may recall the bit about how many barrels the Great White can have attached to it and still sound – well, that is what the outsize float is all about! The pollack has to pull the float underwater which acts as a brake, and of course the extra resistance will also conspire to sink the hook in well. You may say ‘doesn’t my drag act as a brake?’ Well, of course it does, but the float works its magic in those crucial few seconds immediately after the fish takes the float under and you are still winding in slack line.

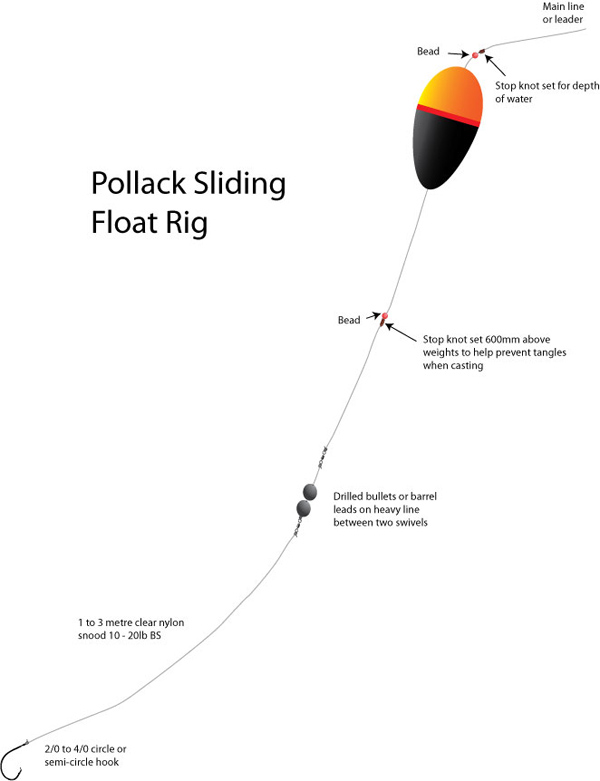

A Power Gum stop knot on your mainline sets the depth, and you put a small bead just above the float to stop the knot slipping inside the tube. Next comes the sliding float, an ounce or two of lead (usually a bullet) to cock it, followed by a rubber bead to protect your knot from the lead, a swivel and a 3 foot length of 20-30lb fluorocarbon, or clear mono attached to a single hook.

Hooks to suit

Moving onto the subject of hook pattern, I recall a day spent experimenting with Davy Holt, skate and spurdog maestro, using circle hooks for spurs – and finding them to be an abject failure! Of course we knew they must work for something, otherwise commercial long-liners wouldn’t favour the pattern, and I’ve since found grab-and-dive fish like the pollack are more sensible species to employ a circle or semi-circle against.

The 5/0 ‘Tournament Circle’ from UK Hooks is well suited to this method of pollacking. I also love the chemically-sharpened Mustad Big Gun, in about a 2/0, though it is a pretty beefy hook in terms of the wire, but with a wickedly curved, razor-sharp point that gets your pollack in the jaw more often than not. This is important as I am a firm believer in returning the bigger fish, to leave the breeding population intact.

If I hook a granddaddy pollack, one of the biggest thrills is grabbing a trophy shot or two, then watching him swim off with a contemptuous flick of his tail, back to terrorise the local sandeel population!

My preference is to fish the sliding float from an anchored boat – you can do it on the drift but if the boat is moving at any sort of speed, you will tend to find the float rides up the line and fishes shallower than you want it to. At anchor, with the tide running hard, sometimes you can just drop it straight over the stern – and what a thrill it can be if a biggie takes while it’s still close by and you can see that big old float zip underwater at a rate of knots then just stop a few feet sub-surface!

Usually, though, I work out which way the tide is running and cast the float uptide, parallel to the anchor rope, then let it describe an arc round the back of the boat. That covers more water, but you have to bring it in once it’s begun to hold in one position, otherwise the float slides up the line, the bait rises in the water, and before long some pesky seagull has spied it and started madly apple-ducking!

Bait preferences

Bait-wise, live sandeel is the bee’s knees – though up here we would go pollack fishing maybe twice a year if we relied on catching launce – but good quality frozen sandeel isn’t half bad either. Mackerel strip is a routine offering, with red rag a close second. Rag comes into its own when there are just too many bait-grabbing mackerel about. That said, mackerel belly doesn’t seem to interest coalfish so much, so if it’s coalies that are the problem, belly strip will be hot, red rag not.

A tip here is to use belly strip of mackerel- this may seem to be just another bit of a fish flesh, but believe me, it’s the prime cut where pollack are concerned. Whereas mackerel is generally a ‘scent’ bait, the silvery belly strip is all about flutter and movement. That’s why – though you would change a normal mackerel bait frequently – if your belly strip is moving just right you might use the same piece all day, as the scent is a very poor secondary consideration to the movement.

Only the very central part of the belly should be used for best results as the flesh thickens up considerably away from that area, though when short on bait I’ve found that standing (lightly!) on a thicker bit so it is partially mashed will make it work far better… hey, it works for me!

If it’s one of those days where there are pollack galore and bait supplies are very limited, try shallow filleting the sides off a mackerel, maybe 3mm deep – it won’t be as neat as proper belly strip unless you’re a surgeon, but it will still catch.

One final tip – hang on as late into the evening as you can – for the biggest, baddest pollack in the pond usually plucks up the courage to bite just as the sun slips over the horizon!